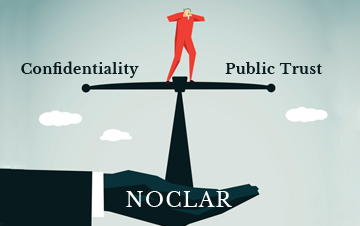

NOCLAR demands careful weighing by Canadian Accountants

New IESBA ethics standard addresses client confidentiality vs. public interest

OTTAWA – For Canadian accountants, a long-standing tradition of practitioner-client confidentiality may, in certain instances, need to be forsaken as a result of new requirements in the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, which addresses non-compliance with laws and regulations (NOCLAR).

Chartered Professional Accountants may be unsure about the balance between client confidentiality on one side and public interest on the other.

Responding to Non-compliance with Laws and Regulations is an international ethics standard for auditors and other professional accountants, and was issued by the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA), an independent standard setting body under the auspices of International Federation of Accountants (IFAC).

The new standard came into effect on July 15, 2017. “While the IESBA Code has not been adopted in Canada, the provincial rules of professional conduct must be as stringent as the IESBA Code, unless there is a legal, regulatory or public interest reason for differences,” says Michele Wood-Tweel, vice-president of regulatory affairs at CPA Canada.

“The CPA profession’s public trust committee is actively considering the NOCLAR changes to the IESBA Code in relation to the CPA profession’s existing ethical standards in the provincial rules of professional conduct and within the context of Canadian laws, regulations and the public interest,” she adds.

“The IESBA has established clear expectations for professional accountants in responding to non-compliance with laws and regulations, representing an important contribution to the public interest,” said Arnold Shilder, chairman of the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) in a press release.

The Canadian accounting perspective

NOCLAR tries to identify situations where it is in the public’s interest to override the principle of confidentiality. However, the primary intention of NOCLAR is not for the practitioner to be able to override and report to an outside party — rather it is to try to remedy the problem before it escalates into a major issue, explains Gary Hannaford, a current member of the IESBA, and the former CEO of CPA Manitoba.

“Confidentiality is, and continues to be, one of the major fundamental principles of the profession. It’s one [through which] a professional accountant is able to establish [and] maintain trust with their clients over the years,” elaborates Hannaford, now a resident of Belleville, Ont.

Moreover, he notes, NOCLAR is only meant to apply to significant situations affecting the public interest.

“It’s not every time there’s some little thing that might go wrong that you’re going to start reporting to the outside body. That turns the profession into much more than what it ever would want to be in this type of situation. We’re not intended to try to be monitoring in a police state,” he stresses.

Practitioners and the public interest

Internationally, the provisions of NOCLAR have been enacted in two ways. The first was within the International Standard on Auditing 250, Responding to Non-Compliance with Laws and Regulations, issued by the IAASB. The second was through the IESBA’s Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, says Dawn McGeachy, a licensed public accountant and partner with Colby McGeachy Professional Corporation in Almonte, Ont.

Domestically, so far, only the auditing provisions have been adopted, as CAS 250. This has implications for CPA practitioners who perform audits, McGeachy adds.

“If an auditor becomes aware of an act or suspected act of NOCLAR committed — or about to be committed — by the entity, there are audit procedures that are required to be performed. They must evaluate the possible effect of the NOCLAR on the financial statements, discuss the matter with management or those charged with governance, and evaluate the implications in relation to other aspects of the audit and the audit opinion,” she elaborates.

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the new provisions is that the auditor must also obtain legal advice in certain circumstances, particularly as they may be required to report the NOCLAR to an appropriate outside authority, which at first glance appears to run contrary to the practitioner’s ethical responsibility to their client to keep matters confidential, McGeachy notes.

In fact “there may also be cases where the practitioner will be prohibited from advising the client that they have made a report to an outside organization,” she adds.

NOCLAR: A broad application

There are various examples of situations under which practitioners must already act in the public interest first. Suspected cases of money laundering, under Canada’s federal Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, is one example.

NOCLAR covers a much broader territory.

“Any act of omission or commission, whether intentional or unintentional, that is contrary to the prevailing laws or regulations are considered NOCLAR under the framework,” says McGeachy.

“This includes such acts committed by a client or employer, those charged with governance, management or other individuals working for or under the direction of a client or employer.

"The new standard applies to laws and regulations related to the professional accountants’ training and expertise, such as: laws and regulations that have a direct effect on the determination of material amounts and disclosures in the financial statements; [and] other laws and regulations, compliance with which may be fundamental to the entity’s business and operations, or to avoid material penalties,” she adds.

The IESBA lists several examples of the types of laws and regulations covered in its NOCLAR standard, including: fraud, corruption and bribery; money laundering, terrorist financing and proceeds of crime; securities markets and trading; banking and other financial products and services; data protection; tax and pension liabilities and payments; environmental protection; and public health and safety.

“Take for example, the case of an auditor who ascertains that the client is not in compliance with environmental laws — perhaps it is engaging in illegal dumping,” says McGeachy.

“Let us also consider that the client is a major employer within their community. The auditor approaches management and those charged with governance about their findings but the client refuses to do the right thing. The auditor must now consider whether a report to the appropriate regulatory agency is required, which may result in the company being shut down, creating loss of employment,” she explains.

McGeachy doesn’t believe practitioners will ultimately leave themselves open to professional liability under NOCLAR.

“But certainly a CPA could have a complaint lodged against them for violating confidentiality,” she notes. “The appropriate CPA body will have to open a disciplinary file and make an investigation. Even if the CPA is cleared in the end — for example, covered by the provisions of CAS 250, which clarify that the auditor's duty of confidentiality is not violated in these cases — it would still be an unpleasant experience.”

Tomorrow, guidance for CPAs in public practice, in NOCLAR: The Path Ahead. Jeff Buckstein, CPA, CGA, is an Ottawa-based business journalist.

(0) Comments